The Legacy

King Frederick William IV of Prussia laid the foundations for the Schinkel-Museum in 1842 with his purchase of Schinkel's artistic estate, consisting of almost 3,000 personal sketches and drawings and 14 oil paintings. Over the following years, the museum was established in three rooms in Schinkel's former official residence in the Bauakademie (School of Architecture) and opened in 1844. With this, the Schinkel Museum became one of the first to be dedicated solely to a single artist or architect. During the first decades of its existence, the museum recorded some considerable additions to its collection thanks to contributions by authorities and ministries, endowments and occasional acquisitions. Today, "Schinkel's legacy", housed at Berlin's Kupferstichkabinett (Museum of Prints and Drawings), comprises 5,500 drawings, gouaches, watercolours and prints, the majority by Schinkel’s own hand or after his designs

The History of the Schinkel Museum

A few weeks after Schinkel's death, Frederick William IV expressed the desire to "ensure all Schinkel's pictures and drawings are stored in a manner worthy of the latter's legacy", as Privy Cabinet Councillor Müller wrote to "the deceased's oldest and truest friend", Peter Beuth, on 6th November 1841. Beuth set to work immediately and composed a "promemoria", in which he firmly advocated the purchase of the collection and its amalgamation with other works by Schinkel, stored at various public institutions and ministries. Finally, in January 1842, the Prussian State purchased Schinkel's artistic estate and his collection of plaster casts after ancient models for 30,000 talers from his widow Susanne (née Berger). At the same time, an order was issued to unite "the other drawings and designs by Schinkel already owned by the state" with the collection, "provided that this can be performed without detriment". As a result, over 320 drawings from the Oberbaudeputation (Senior Building Commission), Schinkel's chief place of activity, and just under 80 drawings from the Gewerbeinstitut (Institute of Trade), headed by Beuth, had been added to the legacy by the time the museum opened in November 1844. The collection swelled to approx. 3,700 sketches and drawings by the early 1860s as a result of further contributions from state institutions, private endowments and acquisitions. Meanwhile, the Beuth Collection, containing important Old Master drawings and prints by artists such as Dürer, had been purchased and united in name with the Schinkel Collection ("Beuth-Schinkel Museum").

Chief government building surveyor August Soller and master builder Wilhelm Salzenberg were entrusted with sorting, stock taking and, as far as possible, identifying the Schinkel drawings. The works were then mounted and placed in 66 portfolios, which were subsequently made available to museum visitors on two days a week for a two-hour period. The museum enjoyed considerable popularity, with over 150 portfolios shown to visitors in 1844, a figure which thereafter increased to around a thousand annually.

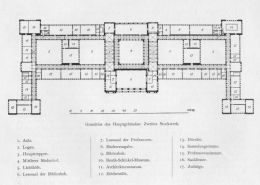

The Schinkel Museum existed in the form described above until the early 1870s. Both a shortage of space and a decline in the appreciation of Schinkel's works resulted in the clearance of the hall containing the plaster casts in 1872, and to the collection's consolidation. Later on, the collection was relocated to the ground floor of the Bauakademie, subsequently moving to the Technical University's new premises in Charlottenburg (now TU Berlin) during the academies' relocation in 1884. It remained independent, and, together with the Beuth-collection, occupied the Southern wing of the main building. The newly founded Architekturmuseum (Architecture Museum) was located in the Esat wing. The now-called Beuth-Schinkel-Museum continued to serve as a teaching and study collection and re-entered the public eye when the Nationalgalerie (National Gallery) exhibited loans from this museum during the centennial exhibition in 1906.

The centennial exhibition heralded a reappraisal of early 19th century art. The advent of Modern Architecture and New Objectivity after the First World War also played a significant role in reviving interest in Schinkel and his student, Ludwig Persius. The Schinkel Museum was ultimately entrusted to the Nationalgalerie in 1923 at the instigation of Ludwig Justi, who, as Director of the Nationalgalerie, doubtless had a particular interest in Schinkel's paintings. The museum was assigned its own premises on Hardenbergstraße in 1924, which were originally designated for the Rauch Museum, previously located in Klosterstraße (Rauch-Schinkel Museum). However, the museum was never opened due to structural deficiencies.

A further seven years passed until the Schinkel Museum was re-established on the upper floor of the Prinzessinnenpalais (Princess's Palace) on Unter den Linden and ultimately inaugurated on 13th March 1931, which would have been Schinkel's 150th birthday. Thematically-grouped paintings, drawings and sketches exemplified the full scope of his oeuvre. These were complemented by contemporary sculptures and works of applied art in accordance with Schinkel's designs. The portfolios were stored on the ground floor, which also housed the study room. The Beuth Collection and the Rauch Archive were also stored there.

The Palace had to be emptied just two years later, and hopes that the Schinkel Museum could return to the Bauakademie were dashed at the same time. During the Second World War, the collection was evacuated, and eventually stored in the Flak Tower at Berlin's zoo. After the war ended, the majority of the collection was relocated to the Soviet Union, finally returning to Berlin during the major return operations of 1958/59. The Schinkel Museum's drawing collection was moved to the reconstructed Altes Museum (Old Museum) in East Berlin and made accessible for research purposes from 1966 onwards, while paintings which weren't missing or lost found a new home in West Berlin, initially in the Neue Nationalgalerie (New National Gallery) near Potsdamer Platz from 1968, subsequently moving to the Galerie der Romantik (Romantic Gallery) in Schloss Charlottenburg (Charlottenburg Palace) in the mid-1980s. Today, the paintings are housed in the Alte Nationalgalerie (Old National Gallery).

Although the re-establishment of the Schinkel Museum was considered briefly during the restoration of the Friedrichswerdersche Kirche (Friedrichswerder Church), this idea was soon abandoned. Losses of sculptures and works of decorative art, and, above all, issues of conservation, which prohibit the exposure of works on paper to the light for long periods, militated against these plans. As a result, the Schinkel Museum was amalgamated with the Nationalgalerie's collection of drawings. In 1992, it was entrusted to the care of the Kupferstichkabinett, where it is now maintained as an independent element of the collection. Approximately 250 drawings and sketches from the Schinkel Museum have been missing since the end of the Second World War. Several of these recently resurfaced, some of which were re-acquired for the collection, such as two of the famous presentation drawings created for Beuth. This gives cause for hope that other missing works which once belonged to the Schinkel Museum have been preserved and will eventually find their way back to the collection.

References

Paul Ortwin Rave: Urkunden zur Gründung und Geschichte des Schinkel-Museums (Documents regarding the Foundation and History of the Schinkel Museum), in: Jahrbuch der Preußischen Kunstsammlungen (Yearbook of the Prussian Art Collection), vol. 56, 1935, pp. 234-249.

Gottfried Riemann: Das »Schinkelsche Museum«, Schicksal eines Nachlasses ("Schinkel's Museum", the Fate of a Legacy), in: MuseumsJournal, 6/1992, issue 4, pp. 15-20.

Sigrid Achenbach: Die Schinkel-Sammlung im Berliner Kupferstichkabinett (The Schinkel Collection in Berlin's Print Room), in: Die Hand des Architekten. Zeichnungen aus Berliner Architektursammlungen (Schriftenreihe der Bauakademie Berlin, 1) (The Hand of the Architect. Drawings from Architectural Collections in Berlin (series 1, Berlin Bauakademie)), exhibition catalogue, Old Museum, Berlin 2002, pp. 82-100.

Rolf H. Johannsen: »Schinkel's Museum«. Von der Bauakademie ins wiedervereinigte Kupferstichkabinett, in: Hein-Th. Schulze Altcappenberg und Rolf H. Johannsen (eds.): Karl Friedrich Schinkel. Geschichte und Poesie. Das Studienbuch, Berlin-München 2012, pp. 305-328.